On the 3rd of December 1971, Pakistan initiated a series of airstrikes against Indian airbases, triggering the Indo-Pak war. It ended on the 16th of December 1971 with the unconditional surrender of 93,000 Pakistani troops to the Indian military in Dacca (now Dhaka). This marked the end of East Pakistan and the creation of Bangladesh. However, the preceding months were a harrowing nightmare for the people of East Pakistan and the Indian government.

In the shadow of the Cold War, millions endured a tragedy largely forgotten by the world – one that reshaped the map of South Asia in 1971. The tragic memories of this tumultuous period leading to the birth of Bangladesh have resurfaced in 2024. After the overthrow of the Sheikh Hasina government in August, there has been an exponential rise in the persecution of Hindus and other religious minorities under the military-backed caretaker regime, widely believed to have been installed by the United States. History could be repeating itself in India’s neighbourhood, making it crucial to revisit the grim past.

Table of Contents

Operation Searchlight

Pakistan plunged into severe internal turmoil following the December 1970 National Assembly elections, which resulted in the Awami League – having contested only in East Pakistan – winning a majority and being in a position to form a government in United Pakistan. However, as this outcome was unacceptable to the political and military elite of West Pakistan, it did not lead to a peaceful transfer of power, eventually resulting in civil disobedience in East Pakistan.

On the night of 25 March 1971, Pakistan’s military dictator, General Yahya Khan, ordered Operation Searchlight, a brutal military crackdown led by General Tikka Khan, to suppress the uprising in East Pakistan. Awami League leader Sheikh Mujibur Rahman declared the independence of Bangladesh just minutes before being arrested post-midnight. He remained in captivity during the ensuing nine months of bloodshed.

In a poignant 2002 interview, Australian doctor Geoffrey Davis recounted the horrors East Pakistani women faced, describing the widely circulated figures of 200,000 to 400,000 rapes as a severe underestimation. Called to Dacca in 1972 by the International Planned Parenthood Federation and the United Nations, Dr. Davis played a crucial role in performing late-term abortions for raped women. In Dacca alone, he performed around 100 abortions daily. During his six months in the newly created nation, he witnessed the haunting depths of women’s suffering.

The US government, under President Richard Nixon and his National Security Adviser Henry Kissinger, was cognisant of the escalating situation in East Pakistan, but Nixon did not favour an active policy.

As reports of bodies strewn across towns and villages in East Pakistan began to arrive, telephone conversations between President Richard Nixon and Kissinger revealed a disturbingly callous attitude. Both seemed pleased that 30,000 disciplined Pakistani soldiers could control 75 million East Pakistanis. When it came to the issue of pressuring Pakistan, Nixon remarked, “The main thing to do is to keep cool and not do anything. There’s nothing in it for us either way.” Kissinger responded, “It would infuriate the West Pakistanis; it wouldn’t gain anything with the East Pakistanis, who wouldn’t know about it anyway, and the Indians are not noted for their gratitude.”

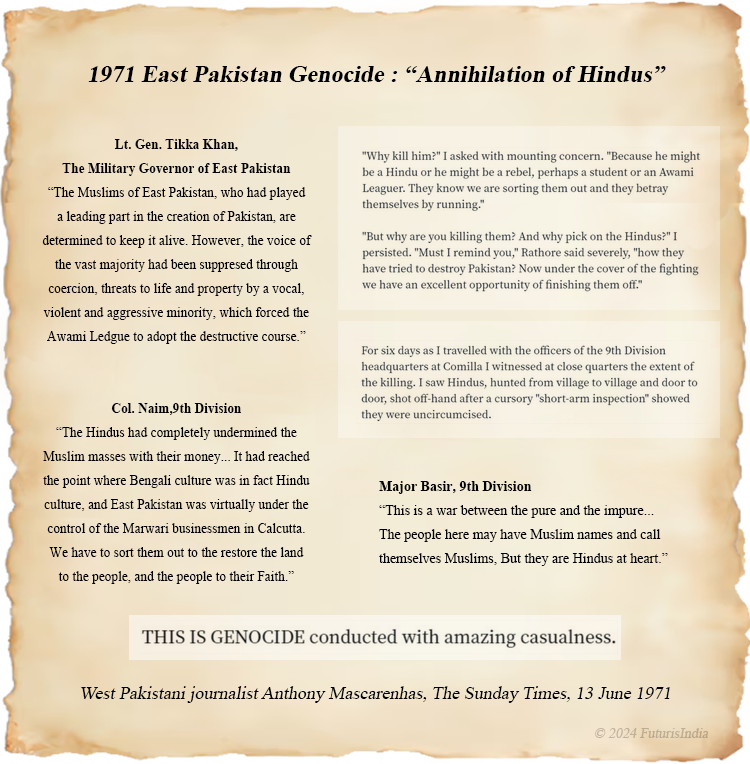

The 1971 East Pakistan Genocide: “Annihilation of Hindus”

British foreign correspondent Simon Dring, who had hid out in Dacca, reported this in London’s The Daily Telegraph on 30 March 1971: “One of the biggest massacres of the entire operation in Dacca took place in the Hindu area of the old town. There the soldiers made the people come out of their houses and then just shot them in groups.”

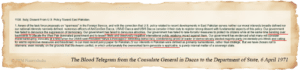

Archer Blood, the US Consul General in Dacca, sent almost daily cables about the dire situation. On 28 March, his cable titled Selective Genocide mentioned, “We are mute and horrified witnesses to a reign of terror by the Pak military” and that “with support of Pak military, non-Bengali Muslims are systematically attacking poor people’s quarters and murdering Bengalis and Hindus. Streets of Dacca are aflood with Hindus and others seeking to get out of Dacca.”

On 6 April, Blood dispatched a dissent cable severely criticising the US administration for wilfully ignoring genocide as an internal matter of a sovereign state. He highlighted the irony that, while the US government was going to great lengths to appease the West Pakistan regime and safeguard Pakistan’s global reputation, the USSR had conveyed a message to Yahya Khan, urging an end to bloodshed. On 8 April, Consul General Blood sent another telegram: “‘Genocide’ applies fully to [this] naked, calculated and widespread selection of Hindus for special treatment… From outset various members of American community have witnessed either burning down of Hindu villages, Hindu enclaves in Dacca and shooting of Hindus attempting [to] escape carnage…”

The 6 April dissent cable, known as The Blood Telegram, exacted a heavy cost from Archer Blood. He was recalled, sidelined, and his career derailed. In one of the Nixon tapes, an enraged Kissinger, in a conversation with Nixon, referred to Blood as ‘this maniac in Dacca’.

The 6 April dissent cable, known as The Blood Telegram, exacted a heavy cost from Archer Blood. He was recalled, sidelined, and his career derailed. In one of the Nixon tapes, an enraged Kissinger, in a conversation with Nixon, referred to Blood as ‘this maniac in Dacca’.

In his 12 April cable, the US Ambassador to India, Kenneth Keating noted, “Pakistan is probably finished as a unified state; India is clearly the predominant actual and potential power in this area of the world; Bangla Desh with limited power and massive problems is emerging.” He conveyed that the United States should condemn military repression in East Pakistan, suspend economic assistance, and cease military supplies to Pakistan. On 15 June, Keating met Nixon and Kissinger in Washington and told them that “when they (Pakistani military regime) started the killing it was indiscriminate. Now, having gotten control of the large centers, it is almost entirely a matter of genocide killing the Hindus.”

Even the Central Intelligence Agency and the State Department, which presented a conservative estimate of casualties, put it at approximately 200,000 midway through the killings.

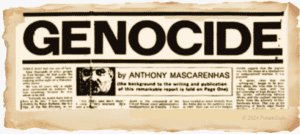

On 13 June, The Sunday Times of London published a gripping exposé titled GENOCIDE, a first-hand account by Pakistani journalist Neville Anthony Mascarenhas that shocked the world. It laid bare the grim truth, shattering Pakistani propaganda. “I have witnessed the brutality of “kill and burn missions” as the army units, after clearing out the rebels, pursued the pogrom in the towns and the villages.”

On 13 June, The Sunday Times of London published a gripping exposé titled GENOCIDE, a first-hand account by Pakistani journalist Neville Anthony Mascarenhas that shocked the world. It laid bare the grim truth, shattering Pakistani propaganda. “I have witnessed the brutality of “kill and burn missions” as the army units, after clearing out the rebels, pursued the pogrom in the towns and the villages.”

“The Government’s policy for East Bengal was spelled out to me in the Eastern Command headquarters at Dacca. It has three elements:-

(I) The Bengalis have proved themselves “unreliable” and must be ruled by West Pakistanis;

(2) The Bengalis will have to be re-educated along proper Islamic lines. The “Islamisation of the masses” -this is the official jargon- is intended to eliminate secessionist tendencies and provide a strong religious bond with West Pakistan;

(3) When the Hindus have been eliminated by death and flight, their property will be used as a golden carrot to win over the under-privileged Muslim middle-class. This will provide the base for erecting administrative and political structure in the future.

This policy is being pursued with the utmost blatancy.”

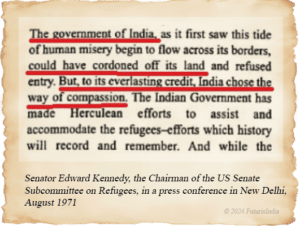

In August, Senator Edward Kennedy visited India as the Chairman of the Senate’s Judiciary Subcommittee on Refugees. At a press conference in New Delhi, following his visit to the refugee camps, the Democrat Senator denounced Pakistan’s military action against the East Pakistani separatists as genocide and attributed the deteriorating relations with India to the ongoing arms aid provided by the US government to Pakistan. He applauded India’s ‘way of compassion’.

In August, Senator Edward Kennedy visited India as the Chairman of the Senate’s Judiciary Subcommittee on Refugees. At a press conference in New Delhi, following his visit to the refugee camps, the Democrat Senator denounced Pakistan’s military action against the East Pakistani separatists as genocide and attributed the deteriorating relations with India to the ongoing arms aid provided by the US government to Pakistan. He applauded India’s ‘way of compassion’.

In his report to the Committee, Senator Kennedy wrote: “Nothing is more clear, or more easily documented, than the systematic campaign of terror—and its genocidal consequences—launched by the Pakistan army” and that the “hardest hit have been members of the Hindu community who have been robbed of their lands and shops, systematically slaughtered, and, in some places, painted with yellow patches marked ‘H’.” Nevertheless, the US government continued to have a soft approach towards Pakistan.

An article in Time magazine dated 2 August 1971 reported that the Hindus, who account for a majority of the dead, have borne the brunt of Muslim military hatred. It quoted a high-ranking US official as stating, “It is the most incredible, calculated thing since the days of the Nazis in Poland.” A 1972 legal study titled The Events in East Pakistan, by the Secretariat of the International Commission of Jurists, stated: “There is overwhelming evidence that Hindus were slaughtered, and their houses and villages destroyed simply because they were Hindus.” Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Sydney Schanberg also reported yellow ‘H’s on Hindu homes and shops, ‘conjuring the Holocaust’.

US Support for Pakistan and its Military Dictator General Yahya Khan

On 7 May, a month after the Blood Telegram, Nixon wrote to Yahya Khan expressing sympathy for the challenges he faced, and attributing the growing opposition to US assistance to the ‘civil strife’ in East Pakistan:

“I understand the anguish you must have felt in making the difficult decisions you have faced… As you are probably aware, some opposition has been expressed among our public and in our Congress to continuing economic and military assistance to Pakistan under present circumstances. This was due largely to the circumstances of civil strife which will hopefully continue to subside. Further, it is to no one’s advantage to permit the situation in East Pakistan to lead to an internationalization of the situation.”

During the Washington Special Actions Group (WSAG) meeting later that day, Kissinger noted, “The President is eager to avoid any break with Yahya.” A week later, he told Ambassador Keating that “the President has felt that we should give President Yahya a few months,” “the President has a special feeling for President Yahya” and “ten days ago when we had received reports that India might be considering military action the President had said he would cut off economic assistance if India moved.”

The focus of the US administration was to uphold the territorial integrity of Pakistan and to keep Yahya in power. Kissinger stated that India does not have “a right to invade Pakistan no matter what Pakistan does in its territory.” It is a different story that America has consistently failed to adhere to that counsel in its own actions.

The focus of the US administration was to uphold the territorial integrity of Pakistan and to keep Yahya in power. Kissinger stated that India does not have “a right to invade Pakistan no matter what Pakistan does in its territory.” It is a different story that America has consistently failed to adhere to that counsel in its own actions.

Nixon’s affinity for Yahya, his aversion to encouraging secessionist movements within an allied nation, his antipathy towards democratic India, and his desire for a rapprochement with China all shaped US policy in the region. As a result, the US not only refrained from condemning Pakistan or leveraging its influence to stop the carnage but also actively supported Yahya’s regime. Amid the reign of terror in East Pakistan, the United States supported a military dictatorship to further its strategic interests, ignoring the humanitarian crisis.

The American Tilt

The US tilt towards Pakistan was in reality a tilt towards China, with General Yahya Khan serving as an intermediary in America’s secret outreach to Beijing. Declassified US documents suggest that, “Since the beginning of his presidency in early 1969, and even earlier, Nixon had been interested in changing relations with China, not least to contain a potential nuclear threat but also, by taking advantage of the adversarial Sino-Soviet relationship, to open up another front in the Cold War with the Soviet Union.” Although Kissinger was exploring at least two other channels to engage with China, given that Nixon had conveyed a message to the Chinese Premier through Pakistan in January 1971, the US was unwilling to upset Yahya while awaiting a response.

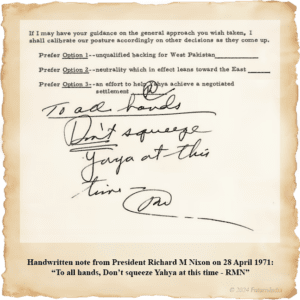

On 27 April, Kissinger received Chinese confirmation through Pakistan, inviting either the US President or his special envoy to Beijing for direct talks. Nixon’s response, recorded in a National Security Council memorandum, was clear: “To all hands, don’t squeeze Yahya at this time – RMN.”

On 27 April, Kissinger received Chinese confirmation through Pakistan, inviting either the US President or his special envoy to Beijing for direct talks. Nixon’s response, recorded in a National Security Council memorandum, was clear: “To all hands, don’t squeeze Yahya at this time – RMN.”

In July, Kissinger secretly travelled to China, flying from Islamabad. Just before the trip, Kissinger assured India that “under any conceivable circumstance the US would back India against any Chinese pressures” and that “In any dialogue with China, we would of course not encourage her against India.” However, as this article later discusses, the US actively encouraged China to open a front against India.

On the 15th of July, Nixon announced a summit with China scheduled for early 1972. During a White House staff briefing meeting on 19 July, Kissinger joked, “The cloak-and-dagger exercise in Pakistan arranging the trip was fascinating. Yahya hasn’t had such fun since the last Hindu massacre!”

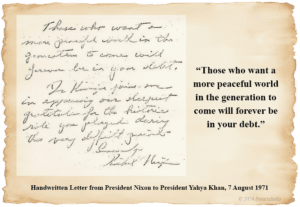

On 7 August, Nixon sent a handwritten letter to Yahya, thanking him for facilitating the Kissinger trip to China. Nixon’s message to the architect of the East Pakistan genocide was telling: “Those who want a more peaceful world in the generation to come will forever be in your debt.”

On 7 August, Nixon sent a handwritten letter to Yahya, thanking him for facilitating the Kissinger trip to China. Nixon’s message to the architect of the East Pakistan genocide was telling: “Those who want a more peaceful world in the generation to come will forever be in your debt.”

On 9 August, India signed the Friendship treaty with the Soviet Union, which Kissinger described as a ‘bombshell’ intended to offset the US-Pakistan-China axis and to prevent American and Chinese intervention.

President Richard Nixon’s pursuit of a historic breakthrough with China came at a profound human cost – three million casualties in East Pakistan, along with the suffering of millions more whose lives were devastated during that dark period. Moreover, it pushed a non-aligned democracy closer to the USSR, forging a lasting friendship that is now unpalatable to the US as it tilts towards India to counterbalance China. This cold prioritisation of strategic interests over human rights and democratic values is a fundamental trait of US foreign policy, evident in varying degrees in every American administration.

Antipathy Towards India

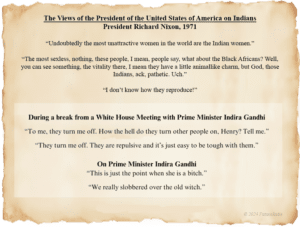

The US policy was driven by cold strategic calculations as well as fuelled by Nixon and Kissinger’s repulsion towards Indians and India. In May end, when India was dealing with a massive inflow of refugees from East Pakistan, the President of the United States, driven by his blind hatred, was hoping for a mass famine in India.

“Nixon: The Indians need—what they need really is a—

Kissinger: They’re such bastards.

Nixon: A mass famine.”

In November, during a break from the meeting with the visiting Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi, Nixon called her a ‘bitch’ and ‘witch’, and Kissinger followed by calling her a ‘bitch’ thrice.

“Nixon: This is just the point when she is a bitch.

Kissinger: Well, the Indians are bastards anyway… They are the most aggressive goddamn people around there.”

Notably, at that time, India was hosting 9.8 million East Pakistani refugees, 93 per cent of whom were Hindus.

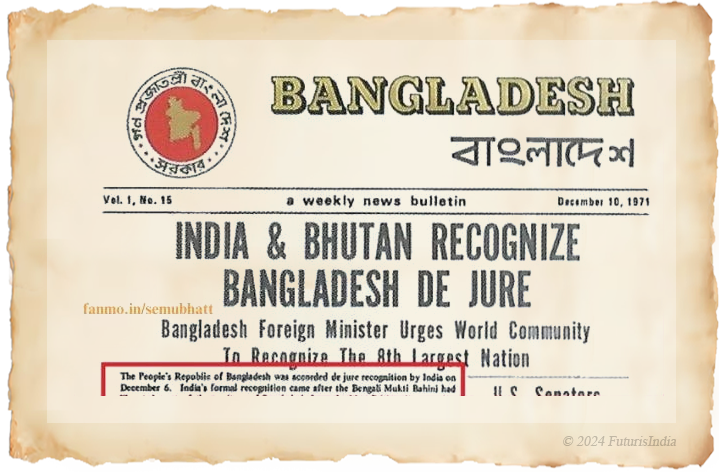

The 1971 India-Pakistan War and Bangladesh Liberation

At 17:40 on 3 December 1971, Pakistan launched Operation Chengiz Khan – preemptive air strikes on eleven Indian air bases. Indian Prime Minister Indira Gandhi declared this an act of war. Counter-air strikes were launched that night, marking the start of the 13-day Indo-Pakistan War, one of the shortest in history. The war concluded on 16 December with the surrender of 93,000 Pakistani soldiers to the Indian army and the signing of the Instrument of Surrender by Pakistan’s Eastern Command in Dacca. Bangladesh was liberated. India had already recognised Bangladesh on 6 December.

Portraying India as the Aggressor in the 1971 War

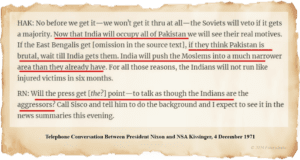

On 3 December, when Kissinger informed Nixon about the Pakistan Air Force’s attack on the Indian Air Force bases, Nixon said, “Pakistan thing makes your heart sick. For them to be done so by the Indians and after we have warned the bitch.”

The United States blamed India’s uncompromising stance and its interference in East Pakistan for provoking the war. America’s primary concern was safeguarding West Pakistan, fearing the potential damage to the US image if a ‘Soviet stooge, supported with Soviet arms’, were to overrun an American ally. Nixon administration feared that any perceived weakness in supporting Pakistan could undermine the reliability of the US as an ally and impact the evolving dynamics with China. In his 1979 memoir, Kissinger noted, “Since it was a common concern about Soviet power that had driven Peking and Washington together, a demonstration of U.S. irrelevance would severely strain our precarious new relationship with China.”

While the US reinforced its support for Pakistan, it simultaneously sought to frame India as the aggressor.

8 December

Nixon: “I may just have to go on in a press conference, to [meet] the press on this subject, and say they [Indians] are aggressors.”

10 December

Nixon: “I don’t want the Indians to be happy… I want a public relations program developed to piss on the Indians.” “I want to piss on them for their responsibility. Get a white paper out. Put down, White paper. White paper.” “I want the Indians blamed for this, you know what I mean? We can’t let these goddamn, sanctimonious Indians get away with this.”

12 December

Nixon: “…if this Indian action against the West continues against the overwhelming weight of the world public opinion, then I will have to make a public statement labelling India as the aggressor, as a naked aggressor… You see the thing I feel is that the Indians are susceptible to this world public opinion crap.” The US President explained that ‘the propaganda’ was important as it would help with the Chinese, put heat on Russia and ‘goddamn Indians’, and support him domestically as he was facing severe criticism.

Senator Edward Kennedy said that the Administration was making India “the scapegoat of our, frustrations and failures and of the bankruptcy of our policy toward Pakistan.” He added, “Our Government and the United Nations must come to understand that the actions of the Pakistan Army on the night of March 25 unleashed the forces in South Asia that have led to war.”

The Flow of US Military Aid to Pakistan in 1971

Despite the Pakistani army, equipped with American weapons, committing mass atrocities in East Pakistan from 25 March onwards, the United States sent ten ships with military cargo to Pakistan, circumventing the loosely enforced embargo in April. By July, the United States was the only Western nation supplying military goods to Pakistan. In October, West Pakistan diverted $10 million in US humanitarian aid, originally intended for East Pakistan relief, for military purposes.

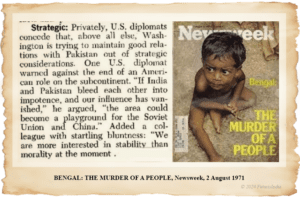

Newsweek’s issue of 2 August reported, “Washington’s equivocation has already enraged India, where most officials are convinced that Yahya could not continue his policy of repression without outside help,” adding that the arms supply to Pakistan “amounts to condoning genocide in Bangladesh” and could harm Indo-US relations. The magazine also noted that the United States’ approach was perceived as indifference to the human suffering in Bangladesh.

Newsweek’s issue of 2 August reported, “Washington’s equivocation has already enraged India, where most officials are convinced that Yahya could not continue his policy of repression without outside help,” adding that the arms supply to Pakistan “amounts to condoning genocide in Bangladesh” and could harm Indo-US relations. The magazine also noted that the United States’ approach was perceived as indifference to the human suffering in Bangladesh.

The Indian Ministry of External Affairs’ 1971-72 Annual Report also stated that the US continued supplying arms to Pakistan beyond 25 March 1971, up to November that year, despite assurances to the contrary. On the other hand, the limited quantity of military equipment that was to be sold to India was swiftly cancelled, and when the war began, the US suspended general economic aid to India. The MEA report was scathing of American duplicity: “No Government in the world uses the terms ‘peace’ and ‘freedom’ so copiously as the leaders of the U.S. Administration do on every conceivable occasion. Yet these words seemed to have no meaning for them as it related to the people of Bangladesh.”

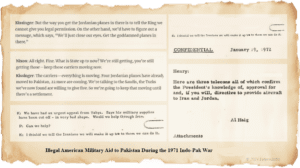

Throughout the war, the Nixon administration also facilitated third-party transfers of US-made fighter jets and military equipment to Pakistan. In a revealing exchange on 8 December, Nixon asked Kissinger in the presence of the Attorney General, “Is it really so much against our law?” before adding, “Hell, we’ve done worse.” On 10 December, Kissinger boasted to the Chinese Ambassador to the UN that, despite being barred by law, arrangements had been made for 26 planes from Jordan and six from Turkey, along with ammunition from Iran, to be delivered to Pakistan. A letter from Deputy NSA Alexander Haig to Kissinger, dated 19 January 1972, confirmed that Nixon had authorised aircraft transfers to Iran and Jordan in exchange for planes for Pakistan. This demonstrated how the US President operated outside legal norms to support Pakistan.

Throughout the war, the Nixon administration also facilitated third-party transfers of US-made fighter jets and military equipment to Pakistan. In a revealing exchange on 8 December, Nixon asked Kissinger in the presence of the Attorney General, “Is it really so much against our law?” before adding, “Hell, we’ve done worse.” On 10 December, Kissinger boasted to the Chinese Ambassador to the UN that, despite being barred by law, arrangements had been made for 26 planes from Jordan and six from Turkey, along with ammunition from Iran, to be delivered to Pakistan. A letter from Deputy NSA Alexander Haig to Kissinger, dated 19 January 1972, confirmed that Nixon had authorised aircraft transfers to Iran and Jordan in exchange for planes for Pakistan. This demonstrated how the US President operated outside legal norms to support Pakistan.

US Escalations: Provoking China and Deploying the USS Enterprise

Among the morally wrong and legally questionable actions taken by the US to support Pakistan’s military dictatorship, two stood out as particularly reckless.

The first was the encouragement of China to open a front against India. On 23 November, the day after the Battle of Boyra – an air battle lasting under three minutes, in which the Indian Air Force shot down three Pakistani jets – Henry Kissinger and George Bush (US Ambassador to the United Nations) met with Huang Hua (Chinese Ambassador to the UN). During this meeting, Kissinger disclosed that the Indian Army had moved two mountain divisions from the Chinese border to East Pakistan, and offered to share additional sensitive information, subtly encouraging China to take military action against India.

In two meetings on the evening of 8 December, President Nixon expressed strong interest in involving China in the Indo-Pakistani war, even if that risked provoking the Soviet Union. “Boy, I tell you a movement of even some Chinese toward that border could scare those goddamn Indians to death.” “Yeah, but you know we can’t do this without the Chinese helping us. As I look at this thing, the Chinese have got to move to that damn border. The Indians have got to get a little scared.” On 10 December, Nixon told Kissinger, who was to meet the Chinese later: “Could you say that it would be very helpful if they could move some forces or threaten to move some forces?” “Now goddamn it, we’re playing our role and that will restrain India. And also tell them that this will help us get the ceasefire.”

The statements of Kissinger to Ambassador Huang Hua provide an insightful window into American thinking and manoeuvres during the 1971 Indo-Pak War:

- “If the People’s Republic were to consider the situation on the Indian subcontinent a threat to security, and if it took measures to protect its security, the US would oppose efforts of others to interfere with the People’s Republic.”

- “There is no military equipment going to India. This means specifically we have canceled all radar equipment for defense in the north.”

- “We think that the immediate objective must be to prevent an attack on the West Pakistan army by India. We are afraid that if nothing is done to stop it, East Pakistan will become a Bhutan and West Pakistan will become a Nepal. And India with Soviet help would be free to turn its energies elsewhere.”

- “Our judgment is if East Pakistan is to be preserved from destruction, two things are needed— maximum intimidation of the Indians and, to some extent, the Soviets. Secondly, maximum pressure for the ceasefire.”

- “We want to preserve the army in West Pakistan so that it is better able to fight if the situation rises again. We are also prepared to attempt to assemble a maximum amount of pressure in order to deter India.

Kissinger also informed the Chinese Ambassador that the US was “moving a number of naval ships in the West Pacific toward the Indian Ocean: an aircraft carrier, accompanied by four destroyers and a tanker, and a helicopter carrier and two destroyers.”

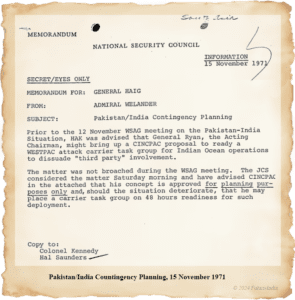

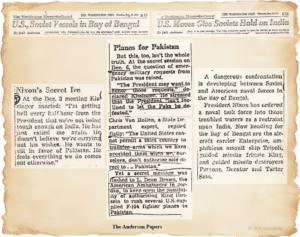

This was the second dangerously reckless step. The US government implicitly threatened India by deploying its nuclear aircraft carrier, the USS Enterprise, to the Bay of Bengal ostensibly for evacuation purposes. This alarming escalation strategy brought the world perilously close to a superpower confrontation, with the Soviets supporting India. It must be noted here that in anticipation of a potential deterioration in South Asia, the Nixon Administration had formed an attack carrier task group in mid-November (see image).

This was the second dangerously reckless step. The US government implicitly threatened India by deploying its nuclear aircraft carrier, the USS Enterprise, to the Bay of Bengal ostensibly for evacuation purposes. This alarming escalation strategy brought the world perilously close to a superpower confrontation, with the Soviets supporting India. It must be noted here that in anticipation of a potential deterioration in South Asia, the Nixon Administration had formed an attack carrier task group in mid-November (see image).

On the morning of 12 December, Nixon, Kissinger, and General Haig discussed the possibility of Soviet military action against China in the event of Chinese military moves to threaten India.

Kissinger: “If the Soviets move against them and we don’t do anything, we’ll be finished.”

Nixon: “So what do we do if the Soviets move against them? Start lobbing nuclear weapons?”

The leader of the free world was casually contemplating a nuclear showdown with the Soviet Union to protect communist China in case it acted aggressively against democratic India at the behest of the US, all to safeguard the genocidal military dictatorship of Pakistan and prove to China that the US could be trusted as an ally.

The Anderson Papers and Diplomatic Concerns over US Escalations

Probably alarmed over the Nixon Administration’s perilous manoeuvres, insiders within the White House leaked the minutes of the Washington Special Actions Group meetings and confidential memorandums to investigative reporter Jack Anderson.

Starting 14 December, Anderson’s columns revealed classified US decision-making in the Indo-Pak War of 1971. These pieces, collectively known as The Anderson Papers, exposed the Nixon-Kissinger inclination toward Pakistan. The White House attempted to discredit the columns, compelling Anderson to release the official secret documents to the press.

Anderson’s groundbreaking investigative work earned him the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, but it also incurred the wrath of the Nixon Administration to a shocking extent. In 1972, two US operatives, testifying under oath, admitted to plotting the poisoning of Anderson at the behest of a high-ranking aide to President Nixon. According to The Washington Post, which had published Anderson’s columns, the plot was aborted, and the conspirators were apprehended a few weeks later in connection with the Watergate break-in.

Anderson’s groundbreaking investigative work earned him the 1972 Pulitzer Prize for National Reporting, but it also incurred the wrath of the Nixon Administration to a shocking extent. In 1972, two US operatives, testifying under oath, admitted to plotting the poisoning of Anderson at the behest of a high-ranking aide to President Nixon. According to The Washington Post, which had published Anderson’s columns, the plot was aborted, and the conspirators were apprehended a few weeks later in connection with the Watergate break-in.

Even the US diplomats and allies were unnerved. On 15 December, US Ambassador to India, Keating, wrote to the White House, “my diplomatic colleagues view deployment of carrier task force as military escalation by US.” He added that Canadian High Commissioner George believes that the US decision to deploy the carrier task force at this time “has served as encouragement to Yahya to continue Pak military effort… Furthermore, George views deployment as direct injection superpower involvement, which [is] bound to increase nervousness of both Soviets and Chinese and likely prompt or serve as screen for their increased involvement.”

Australia’s Foreign Affairs Secretary John Keith Waller characterised the deployment of the Enterprise as ‘an act of egregious stupidity’.

The End of the War and the Lasting Lesson on America’s True Nature

On 4 December 1971, the United States introduced a resolution in the United Nations Security Council (UNSC) calling for a ceasefire and the withdrawal of troops. Both the US and China voted in favour, while the UK and France abstained. The Soviet Union, however, vetoed the resolution, citing the lack of a political settlement in East Pakistan. A second resolution on 5 December met the same fate, with the USSR vetoing it once again. On 13 December, a US resolution was again vetoed by the USSR. India was abandoned by Non-Aligned Movement allies at the UN, with only a few nations that the Soviets could lean upon voting in favour. Notably, the UNSC did not pass any resolutions on South Asia during the nine months of genocide in East Pakistan.

After General AAK Niazi signed the surrender of East Pakistan on 16 December, Indira Gandhi declared a unilateral ceasefire on the Western Front on the 17th. Kissinger rang up Nixon, “Congratulations Mr President. You saved West Pakistan.”

Nixon’s obsession with Pakistan’s President Yahya Khan persisted. On 27 December 1971, Nixon passed a handwritten note to Kissinger, emphasising that Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, the newly appointed President of Pakistan, “must be strongly informed – RN [Richard Nixon] will be very opposed to the trial of Yahya.” In an ongoing display of moral bankruptcy, the President of the United Nations sought to shield the Pakistani military ruler, who was responsible for the suffering and death of millions in East Pakistan.

In 1971, India not only inflicted a decisive military defeat on Pakistan but also outmaneuvered the formidable United States and its most renowned strategist, Henry Kissinger. The US reputation suffered in all three nations involved – in India, for siding with Pakistan and adopting a hostile stance; in Pakistan, for failing to prevent the loss of East Pakistan; and in the newly formed Bangladesh, for enabling the genocide. The infamous US tilt estranged the world’s largest democracy, pushing it closer to the Soviet Union. Decades later, the trust deficit continues to mar bilateral ties between the world’s two most important democracies.

In the aftermath of the Indo-Pak crisis, Kissinger assured Nixon that the events would fade from collective memory. His view proved both accurate and flawed. A nation was born, enduring the horrors of mass killings, rapes, and widescale devastation. The American consciousness bears no moral burden regarding the loss and disruption of millions of lives. However, in India, the haunting memories of this tragic chapter persist.

From an Indian perspective, 1971 underscored a fundamental characteristic of the US – the American geostrategic considerations consistently outweigh ethical concerns. Highlighting the discrepancies between the United States’ stated values and its actions in 1971 is crucial, particularly as the US continues to assert itself as the moral arbiter of the world on human rights, democratic values, and the rule of law. India, however, has experienced the impact of US realpolitik decisions.

The respect Henry Kissinger commanded across the US political spectrum – despite being regarded as a war criminal in many parts of the world – further highlights the tendency of American decision-makers to prioritise power over principles. The stark contrast in how the US and India view the events of 1971 is exemplified by Kissinger’s 100th birthday celebration and his subsequent passing last year. His birthday party in May 2023 was attended by influential Americans, including Secretary of State Antony Blinken, CIA Director William Burns, and USAID Director Samantha Power, while his death in November was seen by many in India as a long-overdue reckoning.

The United States’ unwavering support for Pakistan, continued over the decades even as the latter sponsored terrorism against India, including the horrific 26/11 Mumbai attacks, reinforced this belief.

In December 2023, as India remembered the events surrounding the 1971 war, the US hosted Pakistan’s Chief of Army Staff, General Asim Munir, for his first official visit to Washington. Notably, Munir’s visit came within weeks of the United States attempting to portray India as an aggressor, alleging Indian involvement in a murder plot against the US-harboured terrorist Gurpatwant Singh Pannun. This served as a stark reminder that, irrespective of the efforts to strengthen the Indo-US ties and the bilateral bonhomie, the US does not hesitate to cast India in a negative light, perpetuating the same patterns that were visible in 1971.

The Cost of Bangladesh’s Freedom to India

The liberation of Bangladesh in 1971 came at an immense cost to India, both in terms of human lives and economic strain. India lost 3,843 soldiers, with 9,851 wounded, in the war with Pakistan. Beyond this human toll, the economic cost of the war, coupled with hosting millions of refugees, was staggering.

This 1971 East Pakistan refugee movement was one of the largest movements of people in history. By 15 November, 9.8 million refugees – 93 per cent of whom were Hindus – had fled to India. Nearly 6.8 million of the refugees were reported to be in about 1,500 refugee camps, with the remainder staying with friends, relatives, or in public buildings. The World Bank calculated refugee costs to India for the financial year 1971-72 based on the camp population alone – a staggering $700 million, of which $200 million was pledged by foreign donors, including the United States. Even with full delivery of the pledged donation, India faced a $500 million burden, nearly 20 per cent of its planned development budget.

The sheer scale of the refugee crisis placed immense pressure on India’s fragile economy. Development projects were stalled, the Five-Year Plan was reappraised, and new taxes were introduced to manage the financial burden. Indian citizens shouldered the cost of relief and rehabilitation, including a compulsory five-paisa stamp tax on postal articles and state-level surcharges like Maharashtra’s five-paisa levy on bus tickets. The price of Bangladesh’s freedom was borne by Indian soldiers, citizens and economy.

India also continued to play a major role as a donor to the newly formed nation, assisting with the reintegration of refugees. Despite India’s repatriation and resettlement efforts, a significant percentage of refugees ultimately settled in India.

The Enduring Relevance of 1971

In December 2024, Vijay Diwas was marked amid rising tensions with Bangladesh, which is showing eerie signs of a repeat of history.

While Bangladesh gained independence in 1971, the seeds of religious intolerance sown during that era never fully disappeared. In 1951, Hindus made up 22 per cent of East Pakistan’s population, but by 2022, this had fallen to less than 8 per cent. The Vested Property Act, a tool of systemic dispossession, robbed 1 million Hindu households of over twice as many acres of land, representing approximately 5.75 per cent of Bangladesh’s total land area. This legalised loot and marginalisation, compounded by recurring waves of violence, forced millions to flee.

The atrocities against minorities continued even under Sheikh Hasina’s rule, albeit to a much lesser extent. After the removal of the democratically elected Sheikh Hasina government on 5 August 2024, the situation drastically deteriorated. Under the military-backed interim government led by Chief Adviser Muhammed Yunus, there has been an alarming rise in communal violence against minorities, with 2,010 incidents reported across 68 districts in just two weeks following the fall of the Hasina government. Nearly 900 homes and 950 places of business were targeted, alongside 69 places of worship during that period. In October 2024, several attacks on temples and Durga Puja mandaps were reported. Notably, the crown of Goddess Kali at Jeshoreshwari Temple – a gift from Prime Minister Narendra Modi in 2021 – was stolen. Many teachers from religious minority communities have also been forced to resign. In December, Sheikh Hasina, who has been in India since being forced to flee her country, accused the interim regime of orchestrating a systematic campaign of violence against religious minorities: “Yunus has been involved in genocide in a meticulously designed manner.”

Between August and October 2024, Bangladesh also witnessed a sharp rise in the misuse of law, with over 7,500 cases filed, many on dubious grounds. Among these, 1,174 cases targeted 390 prominent figures, including former ministers and MPs, and at least 129 journalists faced charges such as murder, rioting, and extortion. This has raised serious concerns about the regime’s abuse of legal processes to stifle dissent.

The most alarming development under the Yunus-led interim regime has been the resurgence of jihadist elements. Jamaat-e-Islami, involved in the 1971 war crimes against Bengalis, has gained renewed legitimacy. Similarly, the terror outfit Hizb-ut-Tahrir Bangladesh (HuT), whose stated goal is to create an Islamic Caliphate and which was outlawed in 2009, has found a new foothold. The interim government has appointed Nasimul Gani, a founding member of HuT Bangladesh, as home secretary. Mahfuz Alam, a Yunus aide and the architect of the July 2024 revolution, who has alleged ties to HuT, was sworn in as an adviser in November. Alam’s extremist leanings were evident in his public endorsement of a map depicting Assam, Tripura, and West Bengal as parts of Bangladesh. Meanwhile, the Awami League’s student wing, Bangladesh Chhatra League (BCL), has been banned under the Anti-Terrorism Act.

Another matter of concern is Bangladesh’s warming ties with Pakistan. The Yunus government has removed mandatory security clearances for Pakistani nationals and exempted Pakistani cargo from customs inspections, opening pathways for unchecked movement. This increases the risk of ISI operatives and terrorists infiltrating India through porous eastern border, along with the smuggling of weapons, narcotics, and counterfeit Indian currency.

The situation today bears troubling similarities to 1971, with Bangladesh risking the erosion of the very identity it fought to save. Religious minorities are facing violence and displacement, jihadist elements are getting powerful with state backing, and the United States is turning a blind eye to human rights abuses, prioritising its strategic interests over ethical concerns. On 3 June 1971, Henry Kissinger acknowledged India’s concern that, over time, “radicals could take over the resistance movement and ultimately pose greater challenges for India.” This concern remains as relevant today as it was then. Yet, the US administration appears to be ignoring it once again.

The US, which was quick to voice concerns about democracy during the Hasina government, is turning a blind eye to the radical Islamists shaping the future of Bangladesh. This lends credibility to Sheikh Hasina’s claim that the United States orchestrated her removal due to her rejection of the Biden administration’s request to build a military base on St. Martin’s Island to counter China’s influence in the Bay of Bengal.

For India, the echoes of 1971 are hard to ignore. India – which stood by Bangladesh in 1971 at great human, economic, and diplomatic cost – faces hostility from the Yunus regime, and finds itself dealing with a neighbour whose actions threaten its strategic interests and security. While many Bangladeshis still value India, the current trajectory threatens to undo decades of goodwill and friendship. Without a course correction, the consequences could be catastrophic for South Asia as a whole, and for Bangladesh in particular. It would also cast a long shadow over the Indo-US ties. History, if ignored, tends to repeat itself, and the stakes are just as high this time.

As per our Terms of Use, limited content (text and audio-visual) may be shared with proper credit. Full reproduction in any format is strictly prohibited. See Clause 5 for detailed usage and attribution guidelines.